If you’ve been to our shop recently, you’ve probably noticed that things are starting to look a little…pink.

But what’s so great about all that pink stuff? Well, I’m glad you asked.

Allow me to get on my soapbox…

Pink wine, as I like to think of it, is its own unique thing. It’s got all the lightness and finesse of a white wine with just a touch of the red fruit flavors that we love in red wine, combined with a texture that’s all it’s own.

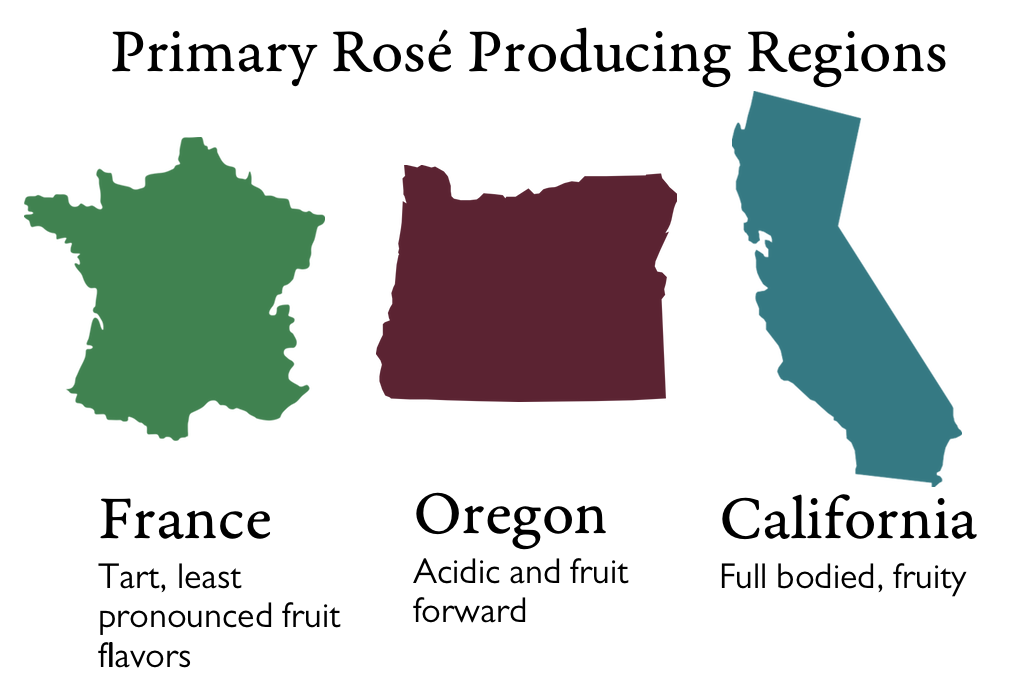

The styles of rosé can often be hard to nail down because color and grape variety are very poor indicators for what the wine will taste like. I prefer to group rosés by region to get a better idea of what they will taste like. French rosés tend to be the most tart and have the least pronounced fruity flavors. I often notice a distinct minerality and an herbal aroma, like sage or tarragon, in rosé from the south of France. The best regions for French rosé are from the south of France, specifically Tavel, one of the few places where only rosés are made. In the USA, Pinot Noir and Pinot Gris rosés from the Willamette Valley in Oregon combine a nice acidic kick with more fruit forward flavors than their French counterparts. Farther south in California the rosés are more full-bodied, fruity, and round in the mouth. You can also find rosés from around the world with vastly varying flavors. I recommend being adventurous and trying as many as you can.

How Rosé is Made

The way a rosé is made can influence the taste and style of a rosé just as much as where it’s grown. There are three main ways of making rosé: the blending method, the maceration method and a third method called saignée.

Blended rosés are most common in Champagne and other sparkling wines from around the world. In this method, before it’s made to be sparkling, the still wine is white and a small amount of red wine is added just before the wine undergoes a secondary fermentation that results in the wine’s characteristic bubbles.

The second method, maceration, can be compared to the process of making tea. Grapes only have color in their skin (the inside is clear, you can check this with a table grape). When the grapes come into the winery and are crushed and the whole mess of grapes and skins are left to sit, sometimes just for a few hours, but sometimes for days depending on the desired style of wine. This time of contact between the skins and the freshly pressed wine is called maceration. Shorter time spent on the skin yields paler, though not necessarily lighter wines. Longer macerations create darker wines with more noticeable tannin.

The third way of making rosé is called saignée (sahn-YAY) in which a winemaker will “bleed” off a bit of wine from their red wine to make it more concentrated. The result can be quite intense with body and tannin closer to red wine than white. You’ll often know that a rosé was made in this method due to its bright pink hue and fruit-heavy aromas.

So which rosé is the best? Well, we’ll leave that up to you to decide, but our answer is all of them, of course! Check out the wines below and see which one piques your interests.