We’ve all heard the term “oak” used to describe wine, and at some point in all of our wine-drinking lives, we’ve internally asked ourselves what that actually means. We’ve also all been at a party in which someone mentions oak in wine and everyone will nod along like they completely understand the concept. But how many of us actually know what oak means for winemaking and can recognize the taste of it wine?

When we say a wine is oaky we are referring to the flavors from the barrels it was aged in. New barrels impart flavors of vanilla, clove, cinnamon, nutmeg, dill, and smoke resulting from the toasting process that allows the barrels to be shaped. As barrels are used over and over again they lose these flavors and become more neutral. The age of the tree the barrel is made from can be very important because as the tree ages, its grains become more tightly packed. The younger tree with more loosely packed grains will impart more flavor into a wine.

You can think of oak in a similarly to salt – a chef will use more or less salt depending upon the flavors he desires in his dishes. The same is true with a winemaker and their desired flavors for their wine.

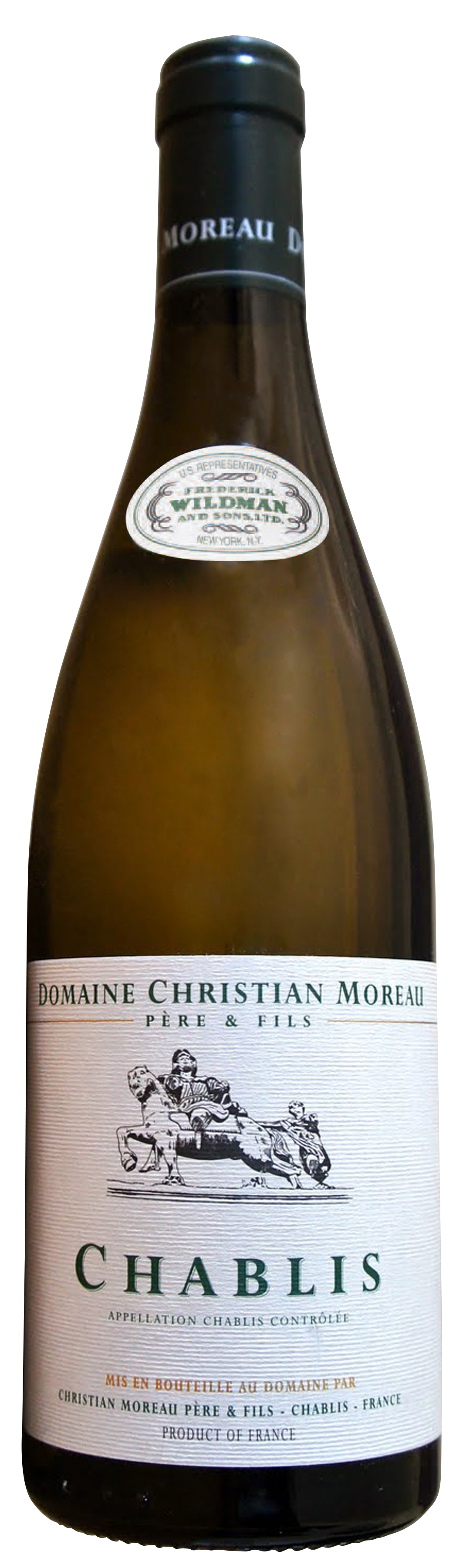

Most people are familiar with oak through drinking chardonnay. Below, we have two examples of chardonnays, both at the opposite ends of the “oak” spectrum.

The first of these is the Christian Moreau Chablis, a chardonnay that is completely unoaked and was made using stainless steel tanks. Because it was never exposed to oak, you’ll get the full, natural flavors of chardonnay: apple, lemon, and a flint-like minerality. It’s color can range from light yellow to hay.

Our second wine, a chardonnay from Rombauer Vineyards, spend nine months in oak barrels and is known for its rich aroma of lemon curd, butterscotch, and vanilla.

As you can, oak plays an important part our industry. Hopefully, next time you’re shopping for wine or tasting with friends, you’ll have a little more insight into what it is you’re drinking.